Labor

Labor or delivery can begin anywhere from the thirty-eighth week of pregnancy up through and including week number forty-two. Your due date is determined by the date of your last menstrual cycle. In most cases you are correct about that date and your healthcare provider will be able to give you a pretty good estimate of when you may go into labor.

Hospital expectations

You may not know what to expect when you arrive at the hospital. First you will be greeted at the nurse’s desk and walked to a birth room (a wheelchair is available for you if you need one). You may be asked to change into a hospital gown. Next, the nurse may assess the baby and labor pattern by using a fetal monitor. Then the nurse may take your blood pressure, temperature, pulse, and breathing rate and perform a pelvic exam.

Once admitted food and drinks may be limited until after the baby is born. You may also need to sign consent forms for the doctor to deliver your baby and perform a circumcision on your baby boy if you desire to have this done. Depending on your labor progress, you may be admitted or observed according to your doctor’s order. If you have pre-admitted, the hospital may already have the information needed to admit you. Someone other than you may be asked to check you in at the hospital registration desk – just as if you made a hotel reservation. The Labor & Delivery nurse may be with you most often. Your nurse is directly involved in your care and reports your progress to the doctor, and the doctor checks on you periodically. Many times your doctor and nurse may review the fetal monitor remotely if the doctor is outside the hospital. The doctor knows your health history and has left specified orders for the nurse to follow so that your care is customized.

Guideline for coming to the hospital:

- When contractions are evenly spaced and approximately five minutes apart and have been that way for at least an hour, and are getting stronger. (Unless instructed differently by your doctor)

- When your water breaks, with or without contractions.

- When you have any of the danger signs of pregnancy.

- Anytime you feel it is necessary.

- Full-term pregnancy.

Stages and phases of labor

Real labor has three distinct stages. The first stage is the longest. This is when the narrow passage way to the uterus opens to let the baby out. For many women this progresses slowly and smoothly over many hours. The muscles around the top of the uterus supply the strength behind the baby. This creates a thrusting action to push the baby out. When the baby passes through the cervix it is similar to getting a tight sweater on over your head. This is the transition to the second stage of labor when the baby travels down the vagina, emerging at the vaginal opening. You will bear down with each contraction to contribute to the strength of the uterus. The journey through the vagina may take up to two hours. When the baby is born, the third stage of labor begins.

Early Phase – this is the longest part of labor but also the least uncomfortable and lasts 2–9 hours. This phase begins with the first contraction and ends when the cervix dilates 3–4 centimeters. The contractions usually are irregular, and you may have a strong contraction followed by a weaker one. You may not know this is true labor. In fact this phase can be confused with false labor. You may most certainly be more comfortable at home during this phase.

Active Phase – this is the beginning of true labor. The contractions are regular (3–5 minutes apart), and no matter what you do they will not stop. The cervix dilates 5–7 centimeters. Most women know they are in labor at this point. Expect cervical progress of 1 centimeter every hour or two for about 3–6 hours. Shaking of the extremities and nausea is normal as the body works hard to dilate the cervix in order for the baby to be born.

Transition Phase – this is the most painful stage of labor. Most women consider this “hard labor”. The cervix dilates 8–10 centimeters. Contractions are 1–3 minutes apart. The pressure you feel in the rectum as the baby descends into the vagina can be overwhelming – like a strong urge to move your bowels. The good news is that this is the shortest phase of labor, lasting 20 minutes to one hour.

You may hear stories about someone who had a one-hour labor. As this is true, there are also women who have 40-hour labors.

Length of labor

The time in labor depends on many things: the size of your baby; the size of your pelvis; the position of your baby in the uterus; the strength of your contractions; the duration of your contractions; the intervals between the contractions; and also your ability to work with labor and not against it.

The early phase of labor is the longest when the cervix is dilating from 1–4 centimeters. This is the most comfortable part of labor, meaning you are aware of cramping in the lower part of your abdomen and possibly your lower back. You may also be using the bathroom more often (loose stools). The active phase of labor is when the cervix dilates from 5–7 centimeters. There is no doubt that you are in labor. The contractions are regular, meaning you can time them at regular intervals. You will feel cramping and a consistent pressure in your lower abdomen. The need to use relaxation and conscience breathing techniques are useful tools now. The transition phase of labor is the shortest length. Your contractions become very intense and concentration on your breathing technique takes every effort on your part and incredible support from your coach.

Signs and length of labor

When contractions first begin, you may question yourself, “Is this it? Am I really in labor?” It is important for you to know the difference between true and false labor. To decide if your contractions mirror true labor, record the time at the start of one contraction and the start of each following contraction. If your contractions are spaced evenly and are occurring closer together, and if walking or changing your position does not give any relief, you are probably in true labor. Only true labor will efface and dilate the cervix. True labor pain increases in intensity; you may lose your appetite and forget about your personal appearance.

The difference between true and false labor contractions is that true labor:

- contractions occur closer together,

- contractions last longer,

- contractions become increasingly more uncomfortable.

With false labor the contractions are:

- irregular with no particular pattern,

- there is no cervical changes,

- there is no descent of the baby.

There is no harm to the baby, but the contractions may be painful and prevent you from resting. Many women gain relief from false labor by walking, rocking in a rocking chair, or your doctor may order a mild pain medication to help you get some rest.

True labor vs. false labor

There are two characteristics of a contraction: frequency and duration.

True labor

- contractions occur at regular intervals

- intensity increases

- intervals shorten

- discomfort experienced in the lower back & abdomen

- pain increases, doesn’t stop with walking or medication

- cervix dilates

False labor

- contractions occur at irregular intervals

- intensity relatively unchanged

- intervals not shortened

- abdominal discomfort

- pain usually relieved with changing position or medication

- cervix doesn’t change

Timing contractions

- Frequency (minutes) – is timed from the start of one contraction to the start of another contraction.

- Duration (seconds) – is timed from the start of one contraction to the end of the same contraction.

Induction of labor

So much emphasis is put on the due date. Half of all first time mothers go past their due date. Unfortunately, family and friends often make things worse when they say things like – “How long is that doctor going to let you go”? Or “Can’t your doctor see your getting so big – that baby needs to come out”! Remember babies are born within a two-week window of your original due date. And as long as your baby is moving normally (10 kicks in an hour) relax and enjoy your pregnancy. It’s easier to care for your baby in utero than when you take them home. However, if your doctor thinks it is better for you to have the baby before natural labor begins, an induction of labor may be recommended.

Your doctor may schedule an induction of labor at one of your office visits. Induction procedures are reserved for pregnancies with special medical needs. After you arrive in the birth unit, your nurse may start an IV (intravenous) and draw blood to be tested as your doctor has ordered. After the nurse establishes the first IV, the nurse will “piggy-back” a second IV that supplies a medication called oxytocin (ox-i-toe-sin). The Oxytocin IV runs through a small infusion pump (computer) that calculates the dosage in milliunit amounts that can be controlled carefully. This amount may be increased or decreased according to your labor requirements. You may find yourself becoming tired or uncomfortable in the last weeks of pregnancy or if your family has arrived and only has one week to visit – these are not medical indications for induction of labor.

Pre-induction treatments – the signs of labor that usually occur in the last month of pregnancy have not happened yet. Your doctor or nurse may insert a prostaglandin medication into your vagina to soften and efface the cervix. This medication may cause contractions like the ones that occur normally in the last weeks before you go into labor. And with some women, this medication may put them into labor. The baby may be monitored via a fetal monitor intermittently or continuously, according to your doctor’s order.

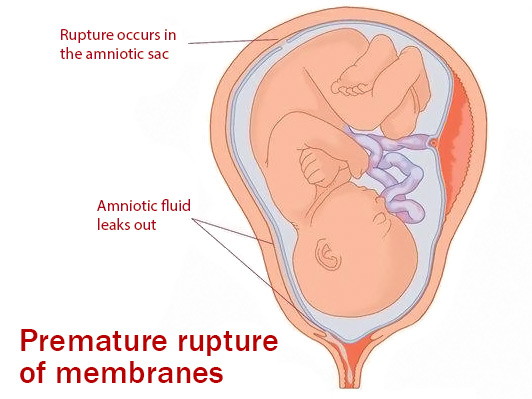

Amniotomy (am-nee-ot-oh-mee) – artificial rupture of membranes. The doctor, midwife or nurse breaks the sac containing the amniotic fluid that surrounds the baby. They use a sterile instrument called an amnihook. The amniotic fluid is straw colored or occasionally may contain meconium (baby’s first bowel movement) that is odorless and green in color. If this occurs, special attention may be focused on your baby immediately following birth to prevent meconium from getting into the lungs. Direct monitoring may be placed by the doctor or nurse to carefully monitor the baby more closely.

Pelvic exam – pelvic, cervical or vaginal exams reveal the condition and changes of the cervix and fetal head. The average exam is done every two hours. However, the need for exams varies from mother to mother. No one likes to endure this procedure, but the exam may proceed easier if you use conscience relaxation and breathing techniques. Most women want to know their progress.

Fetal monitoring

The fetal monitor is a diagnostic instrument used to assess the well being of the fetus – just as the doctor or nurse uses a thermometer, stethoscope or blood pressure cuff to assess your vital signs. You may see two numbers on the monitor screen: the baby’s heart rate and the uterine activity. Your doctor and nurse have special training in the use of fetal monitoring. Remember this is a machine; let the hospital staff worry about the monitoring activity, and you can concentrate on yourself.

Two common ways to monitor the baby in utero:

Indirect or external uterine monitoring – two gadgets are placed externally on your abdomen and held in place by soft elastic belts. One of the gadgets is a sensor that gives information on the fetal heart rate and the other gadget records the uterine activity (frequency and duration of the contraction not the strength of the contraction). The fetal heart rate ranges between 120–160 beats per minute. The numbers on the monitor may vary greatly, and at times the sensor may have a difficult time tracing the baby if you change your position or if the baby moves away from the sensor. This is normal and should be expected. The nurse may adjust the belts and sensor devices for you. Sometimes it looks frightening when the numbers disappear on the machine!

Direct or internal uterine monitoring – the amniotic sac surrounding the baby has to be broke before direct monitoring can be used. Your doctor or nurse may attach the tiniest of filament directly to your baby to record the heart rate. This may be important if external monitoring is not tracing the baby’s heart rate consistently. In order to monitor the uterine activity and strength of the contractions more closely, the doctor or nurse inserts another small soft catheter (cord) into the uterus around your baby – similar to the way you would measure tire pressure with a gauge. Both procedures are performed during a pelvic exam.